Coprime

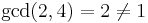

In mathematics, two integers a and b are said to be coprime or relatively prime if they have no common positive factor other than 1 or, equivalently, if their greatest common divisor is 1.[1] The notation a  b is sometimes used to indicate that a and b are relatively prime.[2]

b is sometimes used to indicate that a and b are relatively prime.[2]

For example, 6 and 35 are coprime, but 6 and 27 are not coprime because they are both divisible by 3. The number 1 is coprime to every integer.

A fast way to determine whether two numbers are coprime is given by the Euclidean algorithm.

Euler's totient function (or Euler's phi function) φ(n) for a positive integer n outputs the number of integers between 1 and n which are coprime to n.

Contents |

Properties

There are a number of conditions which are equivalent to a and b being coprime:

- There exist integers x and y such that ax + by = 1 (see Bézout's identity).

- The integer b has a multiplicative inverse modulo a: there exists an integer y such that by ≡ 1 (mod a). In other words, b is a unit in the ring Z/aZ of integers modulo a.

As a consequence, if a and b are coprime and br ≡ bs (mod a), then r ≡ s (mod a) (because we may "divide by b" when working modulo a). Furthermore, if a and b1 are coprime, and a and b2 are coprime, then a and b1b2 are also coprime (because the product of units is a unit).

Another consequence is that if ba-1 ≡ 1 mod a, then a and ba-1 are coprime, hence a and b must also be coprime.

If a and b are coprime and a divides the product bc, then a divides c. This can be viewed as a generalisation of Euclid's lemma, which states that if p is prime, and p divides a product bc, then either p divides b or p divides c.

The two integers a and b are coprime if and only if the point with coordinates (a, b) in a Cartesian coordinate system is "visible" from the origin (0,0), in the sense that there is no point with integer coordinates between the origin and (a, b). (See figure 1.)

The probability that two randomly chosen integers are coprime is 6/π2 (see pi), which is about 61%. See below.

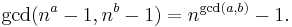

Two natural numbers a and b are coprime if and only if the numbers 2a − 1 and 2b − 1 are coprime. As a generalization of this, following easily from Euclidean algorithm in base n > 1:

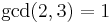

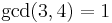

Also, relative primality is not transitive. For example,  ,

,  but

but  .

.

Cross notation, group

If n≥1 and is an integer, the numbers coprime to n, taken modulo n, form a group with multiplication as operation; it is written as (Z/nZ)× or Zn*.

Generalizations

Two ideals A and B in the commutative ring R are called coprime if A + B = R. This generalizes Bézout's identity: with this definition, two principal ideals (a) and (b) in the ring of integers Z are coprime if and only if a and b are coprime.

If the ideals A and B of R are coprime, then AB = A∩B; furthermore, if C is a third ideal such that A contains BC, then A contains C. The Chinese remainder theorem is an important statement about coprime ideals.

The concept of being relatively prime can also be extended to any finite set of integers S = {a1, a2, .... an} to mean that the greatest common divisor of the elements of the set is 1. If every pair in a (finite or infinite) set of integers is relatively prime, then the set is called pairwise relatively prime.

Every pairwise relatively prime finite set is relatively prime; however, the converse is not true: {6, 10, 15} is relatively prime, but not pairwise relative prime (in fact, each pair of integers in the set has a non-trivial common factor).

Probabilities

Given two randomly chosen integers  and

and  , it is reasonable to ask how likely it is that

, it is reasonable to ask how likely it is that  and

and  are coprime. In this determination, it is convenient to use the characterization that

are coprime. In this determination, it is convenient to use the characterization that  and

and  are coprime if and only if no prime number divides both of them (see Fundamental theorem of arithmetic).

are coprime if and only if no prime number divides both of them (see Fundamental theorem of arithmetic).

Intuitively, the probability that any number is divisible by a prime (or any integer),  is

is  (for example, every 7th integer is divisible by 7.) Hence the probability that two numbers are both divisible by this prime is

(for example, every 7th integer is divisible by 7.) Hence the probability that two numbers are both divisible by this prime is  , and the probability that at least one of them is not is

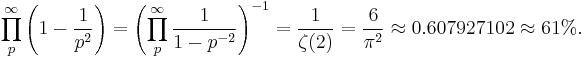

, and the probability that at least one of them is not is  . Now, for distinct primes, these divisibility events are mutually independent. (This would not, in general, be true if they were not prime.) (For the case of two events: A number is divisible by p and q if and only if it is divisible by pq; the latter has probability 1/pq.) Thus the probability that two numbers are coprime is given by a product over all primes,

. Now, for distinct primes, these divisibility events are mutually independent. (This would not, in general, be true if they were not prime.) (For the case of two events: A number is divisible by p and q if and only if it is divisible by pq; the latter has probability 1/pq.) Thus the probability that two numbers are coprime is given by a product over all primes,

Here ζ refers to the Riemann zeta function, the identity relating the product over primes to ζ(2) is an example of an Euler product, and the evaluation of ζ(2) as π2/6 is the Basel problem, solved by Leonhard Euler in 1735. In general, the probability of k randomly chosen integers being coprime is 1/ζ(k).

There is often confusion about what a "randomly chosen integer" is. One way of understanding this is to assume that the integers are chosen randomly between 1 and an integer N. Then for each upper bound N, there is a probabilityPN that two randomly chosen numbers are coprime. This will never be exactly  , but in the limit as

, but in the limit as  ,

,  [3].

[3].

Generating all coprime pairs

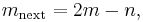

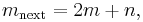

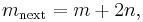

All pairs of coprime numbers  can be generated in a parent-3 children-9 grandchildren... family tree starting from

can be generated in a parent-3 children-9 grandchildren... family tree starting from  (for even-odd or odd-even pairs)[4] or from

(for even-odd or odd-even pairs)[4] or from  (for odd-odd pairs)[5], with three branches from each node. The branches are generated as follows:

(for odd-odd pairs)[5], with three branches from each node. The branches are generated as follows:

Branch 1:  and

and

Branch 2:  and

and

Branch 3:  and

and

This family tree is exhaustive and non-redundant with no invalid members.

References

- ↑ G.H. Hardy; E. M. Wright (2008). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed. ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780199219865.

- ↑ Richard K. Guy (2004). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-20860-7.

- ↑ This theorem was proved by Ernesto Cesàro in 1881. For a more rigourous proof than the intuitive and informal one given here, see G.H. Hardy; E. M. Wright (2008). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199219865., theorem 332.

- ↑ Saunders, Robert & Randall, Trevor (July 1994), "The family tree of the Pythagorean triplets revisited", Mathematical Gazette 78: 190–193.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W. (July 2001), "An alternative characterisation of all primitive Pythagorean triples", Mathematical Gazette 85.

Further reading

- Lord, Nick (March 2008), "A uniform construction of some infinite coprime sequences", Mathematical Gazette 92: 66–70.